As the country's healthcare sector verges on a collapse, UNICEF experts and field teams weigh in on the current need and rapid response in communities.

As Zimbabwe continues to respond to the needs of those affected by Cyclone Idai, which ravaged the country in March of 2019, a highly unstable economy, severe fuel shortages and the lingering effects of drought are putting the country's healthcare sector at risk of collapse.

On top of this, amid warnings from the World Health Organisation that Africa must prepare for an increase in coronavirus infections, the country has gone into lockdown and many UNICEF programs have shifted focus towards preparedness and prevention. The country is still battling to increase mass testing and the number of treatment clinics; adding an unprecedented strain on hospitals.

“It’s estimated that almost half the population of the country requires emergency assistance,” says Laylee Moshiri, UNICEF Representative in Zimbabwe. “That’s a very huge number. This is an emergency situation that needs much attention, although it doesn’t receive what it merits in the global news.”

A lack of physical currency in Zimbabwe has made it hard for the Government to keep up with the import demands for essential goods like medicine and fuel. Ambulances were already scarce before the sector began to deteriorate and many health facilities have no other option but to transport emergency patients - including pregnant mothers - using their own nominated local driver.

UNICEF Zimbabwe's Health Specialist, and former midwife, Shelly, knows the reality of this all too well: “If a woman starts to bleed on you and they are at your clinic, which is even 100kms away, and you don’t get transport, you ask the relatives to run around to look for fuel, to look for transport. Meanwhile the woman has died,” Shelly says.

This issue isn’t only affected by lack of transport. Power outages are common and generators aren’t a viable option given the fuel shortages.

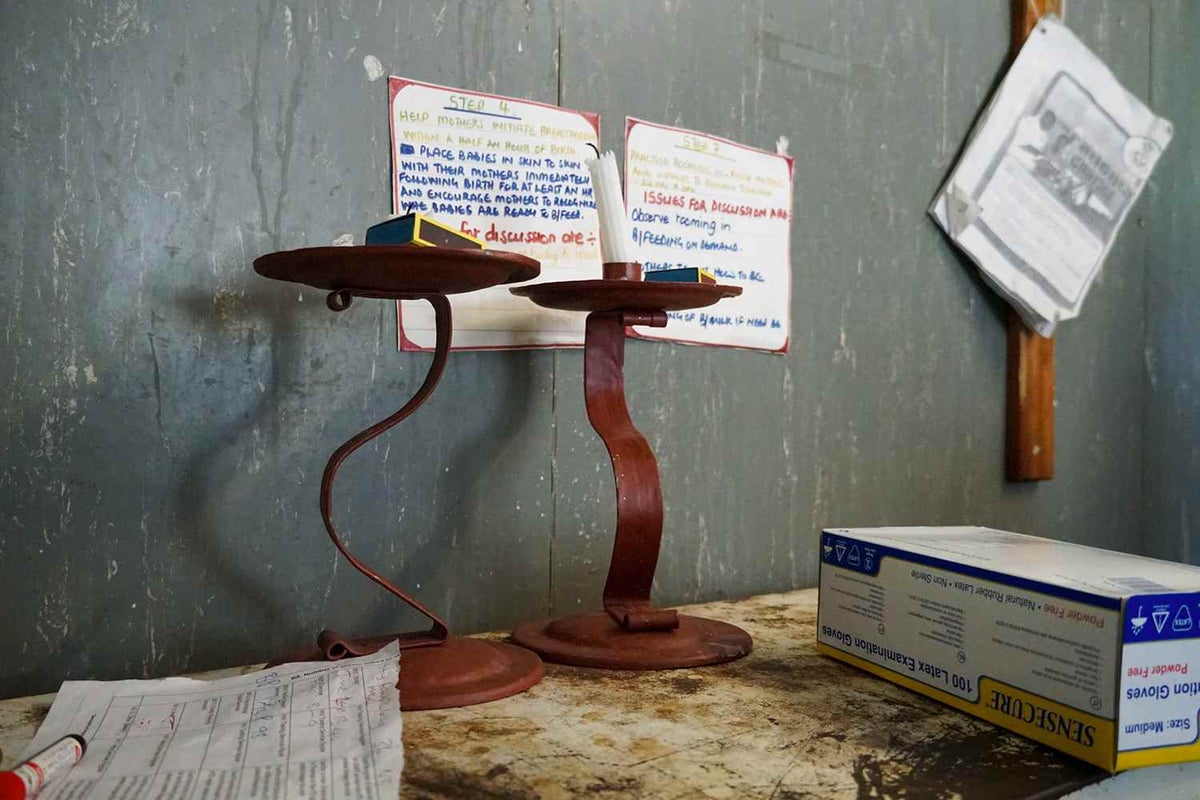

In one labour ward, two melted down candles in the corner of the room are often the only source of light used to deliver a baby at night.

Maternity wings are often dark, small and overcrowded. In the Chiredzi district hospital, three beds in the labour ward cater for the 30 deliveries performed each day. Hospital staff are worried about infection control when women and newborns are living together in such small spaces. This fear is especially pronounced in light of spreading public fear of coronavirus.

One hospital had a bed made, ready for a new mother. The sheets were stained with blood from a previous delivery. But many women are already in labour when they arrive at the hospitals and the blood stains on the sheets aren’t the first thing on their mind.

Sterilisation of essential equiptment and linen is proving extremely hard under these conditions. Power outages mean that hospitals lucky enough to have machines are only able to clean essential supplies sporadically.

Providing essential health outreach is difficult across the dispersed rural villages that the hospitals cater for and transportation is expensive and limited. This means many only arrive once they are in immediate need of care. Women will often need to walk more than 60 kilometres to reach a health clinic only to wait in long lines for beds to become available in the labour ward.

The severe bed shortages extend to maternity wards and most new mothers are not able to spend much time in the hospital before they’re sent home. Many hospitals discharge women and newborns only 24 hours after birth; less than the crucial 72 hours recommended.

UNICEF’s work in the region is helping to provide vital outreach services through community-nominated Village Health Workers. This is alongside our work supporting a clinical mentorship program to upskill rural doctors and medical staff so they can conduct safe deliveries in regional hospitals.

Thanks to health programs like these, maternal mortality is down by almost 30 percent in the last five years. The number of children dying in their first five years is down by nearly the same amount.

But as economic instability threatens the resourcing of healthcare centres, and fuel and water shortages limit the ability to provide adequate care, more newborns are dying.

Last year, under pressures of extreme inflation, healthcare workers stopped coming to work after their salaries were reduced to essentially nothing. Many hospitals weren’t functioning. Thankfully, a local philanthropist stepped in to subsidise wages through scholarships, but this support is due to expire soon and the sector remains in the dark as to the next steps from here.

In the face of these immense challenges, two things remain clear:

- Local health staff are extremely committed to the mothers and children who they serve. Health facilities continue to be vital sources of healthcare and outreach. They know what they need: better facilities, more space, and better information to share with community members who often cannot make the long trip to a clinic. Staff just need the resources to be able to provide the care they desperately want to give.

- UNICEF’s work is absolutely critical to the survival of the sector. Indicators suggest that Zimbabwe may return to the devastating lows of 2008 when hyperinflation led to the printing of the $100 trillion dollar note and a near complete collapse of the health system. Communities know the gaps they face and they’re desperate to fill them.

UNICEF is working hard to help meet these demands to provide for every mother and newborn in urgent need. Mothers and children are dying in Zimbabwe of preventable causes.

The coming years will absolutely be challenging, but there’s no doubt that the continued work of aid agencies will soften the blow otherwise felt by a country in crisis.

“A lot of gains have been made in the last years thanks to support of donors and an importantly critical role that UNICEF has played,” says Laylee Moshiri, UNICEF Representative in Zimbabwe. “Our priority is to make sure those gains will not disappear and those very systems that we have been supporting do not collapse.”

Please consider joining UNICEF to support mothers and children in Zimbabwe. Your donation will help us to provide critical health care services and support that will save lives.

Related articles

Stay up-to-date on UNICEF's work in Australia and around the world