It’s been a relentless, and at times confusing, onslaught of information about how we can protect ourselves and our communities, about the efforts being made by health care workers, and about the incredible advances in science that bring hope for an end to the pandemic.

COVID-19 and vaccines are now part of our daily conversations. But, there are other highly infectious and dangerous diseases that no longer make the headlines, because vaccines have virtually eliminated them from Australia.

These eight diseases may not be common here in Australia but they are certainly still a threat for the world’s children.

1. Tetanus

Tetanus is a very painful bacterial infection which causes seizures, lockjaw and muscle stiffness. People fall ill with the disease when spores are introduced to their bloodstream following a cut or a scrape and about one in 10 people who contract the disease will die. People of all ages are susceptible. But the disease is particularly common and serious in newborn babies and their mums who contract the disease when the umbilical cord is not cared for properly or is cut in an unhygienic way.

Most infants who get the disease will die from it, with neonatal tetanus accounting for more than 30,000 neonatal deaths worldwide each year. Once upon a time in Australia, parents used to worry about tetanus every time their children hurt themselves when playing outside but thanks to vaccines this worry is virtually a thing of the past.

2. Pertussis (whooping cough)

The “whooping” in whooping cough (pronounced ‘hooping’) comes from the sound an infected person makes when they try desperately try to draw oxygen into their lungs following the coughing fits caused by the virus. It is highly contagious and spreads when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Whooping cough can quickly spread through families, childcare centres and schools.

Whilst the vaccine is effective if taken in its full course, people who have been vaccinated against whooping cough can still get the disease — especially if they have not completed the full five doses or had a booster in the last 10 years. It can lead to pneumonia, brain damage and sometimes death. Whooping cough is especially dangerous to babies who are too young to be vaccinated themselves.

Despite a longstanding pertussis immunisation program, and a substantial decline in the disease nationwide, pertussis remains a threat in Australia with around 200 babies too young to be vaccinated hospitalised, and one dying, of the disease each year. Older children and adults who have not received pertussis vaccination are at risk of infection, and are often the source of the life-threatening infection in young babies.

3. Hepatitis B

Worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are at least 257 million people infected with Hepatitis B , of whom only 10 per cent are aware of their infection. Hepatitis B is spread through infected bodily fluids and in areas where it is very common is often passed from mother to child during delivery. One in nine of these children will go on to develop chronic infection which can lead to liver cirrhosis, cancer and death. This is why all pregnant women should be tested for the virus and all babies should receive their first Hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth. Hepatitis B is a baby’s first vaccine, and is truly lifesaving.

4. Polio

Polio not only kills but it cripples. The virus spreads from person to person and can invade an infected person’s brain and spinal cord, causing paralysis. Australia has been free of polio for over 20 years but there are many survivors here given that it was widespread until the vaccine was introduced in the 1950s.

Whilst cases of polio have reduced by 99 per cent worldwide since the vaccine was introduced, polio is still a threat in some other countries, particularly in Afghanistan and Pakistan where the wild virus is on the increase following a COVID-19 induced break in the national vaccination program. Making sure that infants and children are vaccinated is the best way to protect children and prevent polio from returning to our shores.

5. Measles

Whilst your grandparents may remember their parents holding “measles” parties to ensure that all of the neighbourhood’s children got the disease whilst they were young, and in turn earned immunity, measles is a deadly disease that kills. In fact, worldwide measles deaths climbed by 50 per cent from 2016 to 2019 claiming over 207,500 lives in 2019 alone.

Measles is very common in areas of the world where vaccines are difficult to access and a single traveller can cause an outbreak which will spread rapidly through unvaccinated or under vaccinated communities. For all those amateur epidemiologists, measles’s R number (or infection rate) is anywhere from 12 to 17 compared to less than two for COVID-19. Measles is so infectious that it can be passed on up to two hours after an infectious person has left a room.

6. Mumps

Mumps is a viral infection that infects the salivary glands and is best known for giving its victims enormous puffy cheeks and swollen jaws. In the past, mumps infection was very common in childhood in Australia but due to immunisation, it has thankfully become uncommon. For most of those unlucky enough to contract mumps, it will pass without complication, but in boys who become infected at puberty, mumps can cause sterility.

It can also cause inflammation of the brain (encephalitis), the lining of the brain and spinal cord (meningitis), the testicles (orchitis), the ovaries (oophoritis), breasts (mastitis) as well as miscarriage and hearing loss.

7. Rubella

Rubella is spread through coughing and sneezing and is known for its distinctive red rash which appears around two weeks after infection and lasts for three days. Whilst for about half of the people infected symptoms are mild, with some not even realising they’re sick, Rubella is incredibly dangerous for unborn babies and their mums. It can cause miscarriage or cause a baby to be born with births defects including blindness, deafness, heart defects, intellectual disability, impaired growth and inflammation of various organs such as the brain, liver or lungs.

The WHO announced in October 2018 that Australia has eliminated rubella. But elimination does not mean eradication. Outbreaks can still occur if a case is imported from overseas and can spread rapidly through unvaccinated communities, so it is important to continue vaccinating children with the MMR vaccine (which also protects against measles and mumps) to prevent the spread of infection to pregnant women and harm to their unborn babies.

8. Diphtheria

Most of us think of diphtheria as a disease from antiquity that has long since disappeared. Whilst that’s true in many countries that’s to the DTaP vaccine which also protects against tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough), there is an ongoing outbreak in Yemen which has killed thousands. It can cause a thick covering of mucous at the in the back of the nose and throat that makes it hard to breathe or swallow and can cause a patient to suffocate to death if they cannot be put on life support. Tragically, in 2018, a unvaccinated man from Queensland fell ill with the disease after contracting it from a person who has travelled overseas and died.

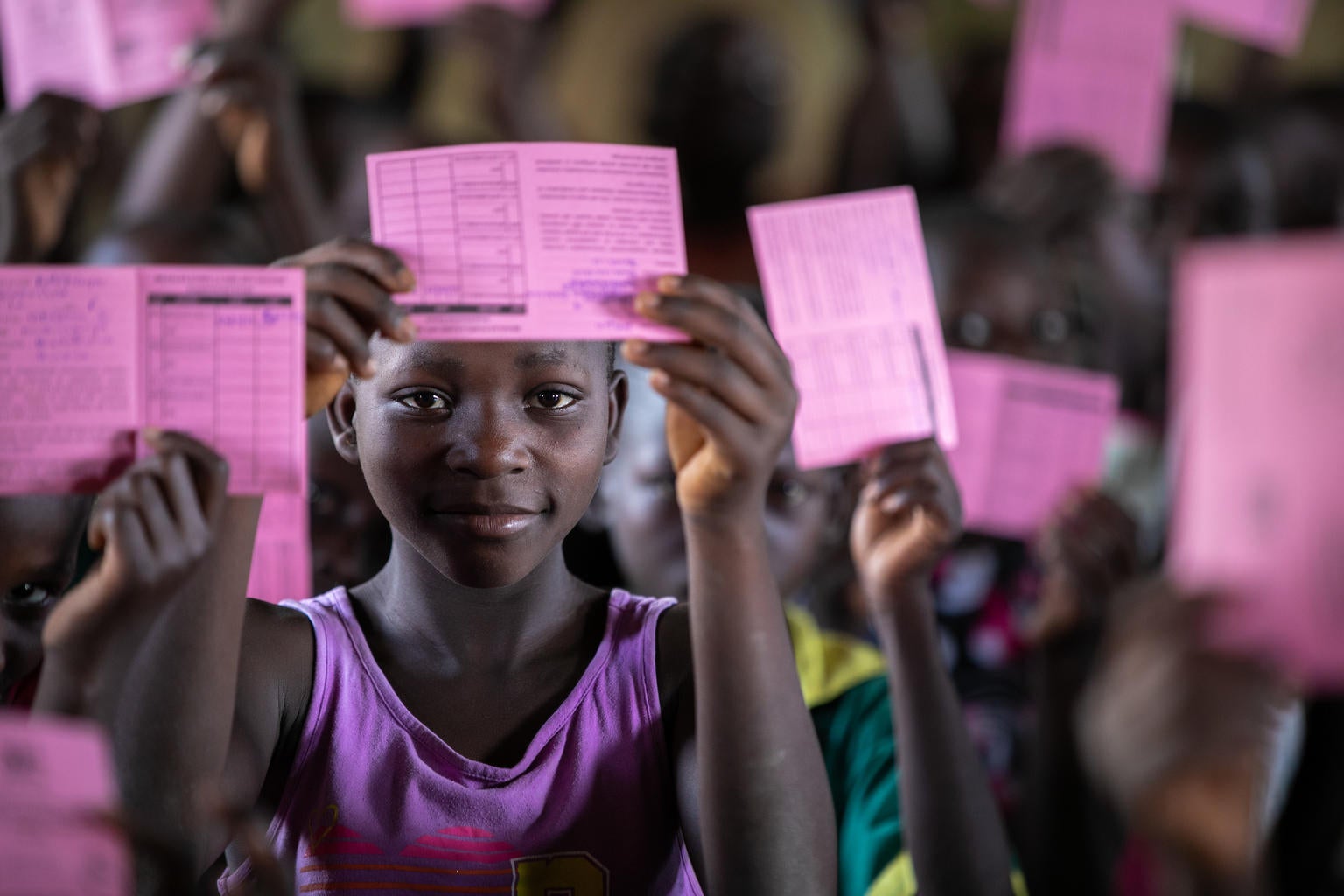

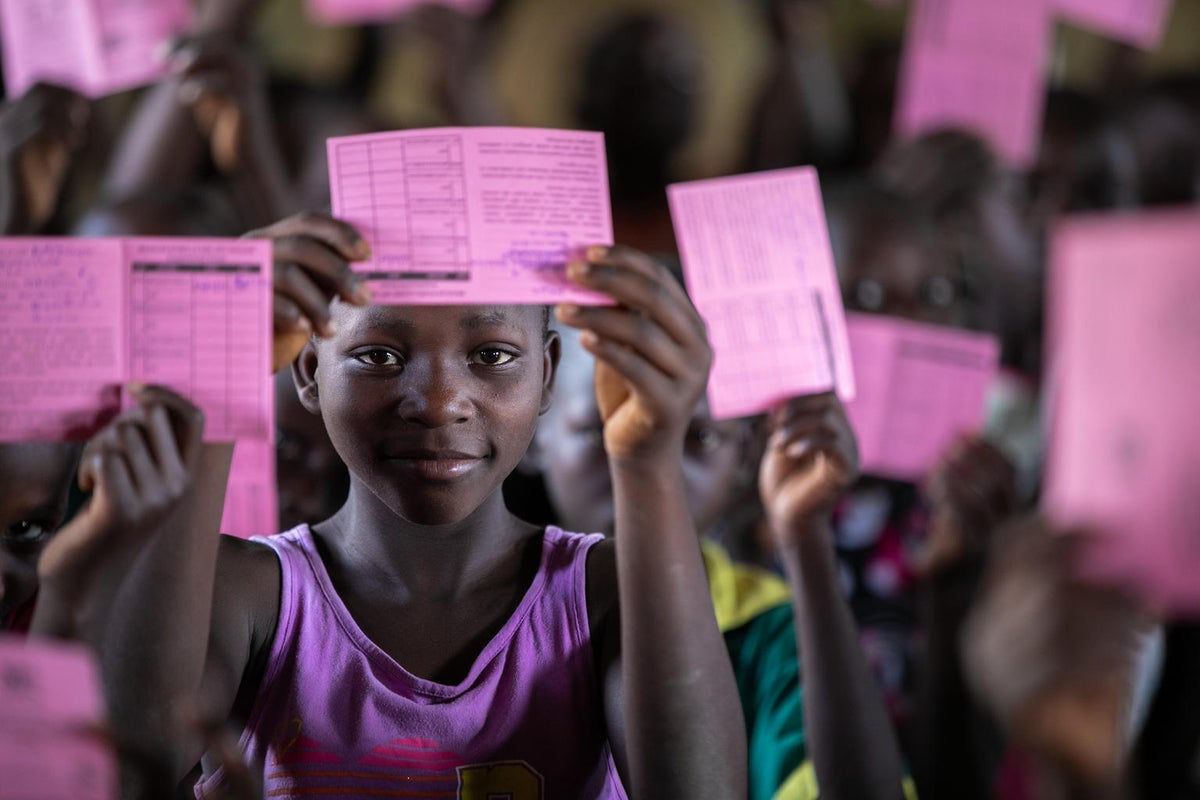

In Australia we are fortunate that our health system is strong and our Government can invest in these critical vaccines, but for those living in countries where not all children can access vaccines UNICEF is there. Each year we vaccinate half the world’s children and protect them from preventable diseases, no matter where they live or what passport they hold. We won’t stop until every child is safe from life-threatening diseases.

Every year, UNICEF vaccinates half of the world's children. Donate now and help us support the children that need it the most.

Donate nowRelated articles

Stay up-to-date on UNICEF's work in Australia and around the world