UNICEF’s humanitarian workers travel to some of the most remote and dangerous places in the world. They make difficult journeys, work long hours, tackle the taboo topics and face unimaginable challenges. There is nothing they wouldn’t do to ensure every child gets a fair chance to live the best life they possibly can.

No workday too long

In a single day, Dr Ri Chol Ok visits between 20 to 30 families in a remote area of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, more commonly known as North Korea. It’s not an easy job, she says, but a new carry bag of supplies provided by UNICEF has made her work a little easier.

“The bag is full of essential medical equipment and medicines which we commonly use, like antibiotics and oral rehydration salts,” Dr Ri says.

“Before, we mostly used herbal medicines - it’s much better now.”

In remote rural areas like Hwasan Ri, children are particularly vulnerable to diseases and illnesses. There are also high rates of malnutrition.

These simple bags are allowing household doctors like Ri to quickly and effectively deliver healthcare to those who need it most, giving young children the chance to survive and thrive.

In addition to the bag, Dr Ri has also received UNICEF supported training, which she says has helped her identify children with nutrition problems. All up, the training was provided to 2,700 household doctors focussing on teaching them how to counsel parents about how best to keep their children healthy and safe.

No topic too taboo

Aaron Moore isn’t afraid to talk about the subjects that make some people cringe. The UNICEF Australia International Programs Manager is focused on improving sanitation habits in communities across the Asia Pacific region. This includes working to end people defecating out in the open and supporting girls and women in ways to improve menstrual hygiene.

“It can be a little bit taboo because these are personal habits that often take place out of sight,”

Aaron says, adding that people in communities he visits often feel uncomfortable discussing where they do or don’t go to the toilet, and once aware of the consequences of going to the toilet in the open, can feel ashamed.

But shame isn’t necessarily a bad thing, he adds, as it quickly gives way to an understanding of the problem and a desire to do something about it.

In Laos for instance, some communities identify those practising open defecation by calling them out in public. While it is uncomfortable, Aaron says, it serves as a powerful motivator for community change, especially since the individual’s behaviour has implications for the whole community.

"Change is often the result of bringing things that are in the dark into the light."

Similarly, UNICEF is working with schools to promote education about menstruation for both girls and boys, and empowering them with the knowledge about the importance of good hygiene.

“This is really crucial because research shows that girls will often drop out of school, or miss large portions of their schooling, once they get their periods,” he says.

“One in three girls in the surrounding region know nothing about menstruation prior to experiencing it.”

“If there is no toilet, or it is dirty and without a lock, and there is no access to water and soap, then girls will miss school when menstruating.”

“Recognising the stigma and inequality girls face in such instances demands we improve awareness and provide better facilities that allow everyone to access a clean and healthy learning environment.”

"Realising there is a problem is the first step in finding a solution."

Reach for the Stars

No distance too far

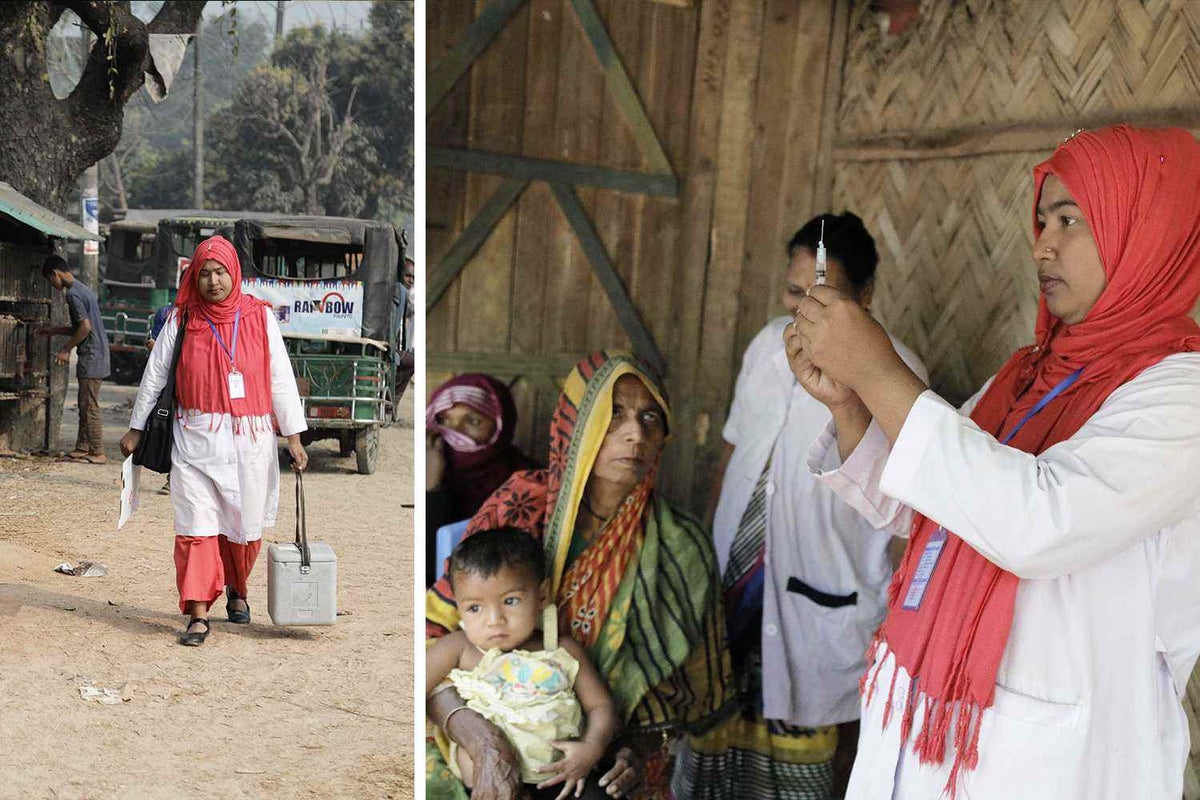

For eight years, four times a week, Sajeda Begum has taken a tuk-tuk and then walked several kilometers with her vaccines to raise awareness about routine immunisation and to vaccinate children against measles and rubella.

Sajeda is determined to prevent disease from spreading in a remote village in Ramu, a sub-district of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

UNICEF believes no child should die of a preventable disease. That’s why we procured nearly 2.5 billion doses of vaccines last year - and are using them globally to protect children.

In Bangladesh, we provide different forms of support to government authorities by strengthening their immunisation systems including helping them acquire vaccines, immunisation training, emergency vaccination campaigns, and communication.

No idea too far-sighted

In Jordan, a country with one of the youngest populations in the world and the second highest share of refugees per capita, Australian Robyn Lui is helping more than 34,000 young people become innovators.

Almost three quarters of Jordan’s population is under the age of 30 and youth unemployment is high. The country is also struggling to accommodate over 650,000 registered refugees – 48% of whom are children.

Robyn and a dedicated team of social innovation facilitators are equipping young people with creative thinking and communication skills that she believes Jordan’s private sector leaders are looking for.

"The great thing about innovation is that if you can imagine it, you can create it. There are no rules in what can be done."

UNICEF Jordan currently runs social innovation programs across Jordan, including the Syrian refugee camps in Za’atari and Azraq.

“People often think ‘innovation’ as products like apps, robots, 3D printers,” she says.

“But social innovation is about creating solutions to address social needs and improve people’s lives.”

A solar phone charger, solar powered washing machines and even a solar powered handheld food blender to help boost nutrition for elderly and babies, are among the list of innovations Robyn has seen from the youth in Jordan, which include a large number of Syrian refugees.

"Some come to the lab very shy at the start and after 12 weeks they want the world to know their name. This, for me that gives me hope that they will be okay despite their uncertain future."

The end goal is helping young people gain the skills and confidence needed to build bright futures for themselves.

Inspired? Even from here in Australia, you can do your bit!

UNICEF humanitarians like Robyn and Aaron do incredible work out in the field but you too can help all around the world by signing up to make a monthly gift & joining our special group of Global Parents.

UNICEF can reach children no one else can. We can provide safe places for children to learn and play, deliver clean water and life-changing supplies, bring a child back from severe malnutrition and make sure every child smiles. But we can’t do it alone. Help UNICEF deliver these things and more to every child.

Related articles

Stay up-to-date on UNICEF's work in Australia and around the world